Southern Sea Otter

Enhydra lutris nereis

Southern Sea Otter

Enhydra lutris nereis

Sea otters once occupied the entire California coastline, but are now restricted to the Central California coast.

Morphology

Southern sea otters belong to the mammal family Mustelidae (weasels, ferrets, badgers, skunks, mink and other otters). They have a long, stout body with a short broad head and snout, and a total body length of about one meter (not including their flat blunt tail). Adult males have an average weight of ~ 30 kilograms, whereas smaller females have an average weight of ~ 20 kilograms. They are unique among marine mammals in having a long tail and paws on their forelimbs.

Habitat and Range

Southern sea otters are currently found along the coast of California from approximately Half Moon Bay to Santa Barbara, and San Nicolas Island. Historically the range extended into Oregon and Baja California, Mexico. They occupy nearshore habitats including kelp forests, sandy seafloor, and estuaries.

Range Map

Reproductive Biology and Life History

Females reach sexual maturity around age 3-4 years, but it takes practice to become a good mother so many females’ first pups don’t survive. Although mating and pupping occur throughout the year, on average across their range, a peak period of pupping occurs from October to January. Females typically give birth to a single pup and provide care to the pup for approximately six months until weaning. Pup rearing and provisioning impose high energetic costs on females since they have to do the caregiving on their own with no help from the males, which requires them to increase the amount of effort that they put into foraging. These single-mom parents are highly susceptible to stressors, such as infections, human disturbance, or mating trauma, which they may endure when they come into estrus post-weaning. The gestation period in sea otters is approximately 6 months, including a 2 month delayed implantation. Delayed implantation is a reproductive strategy in which a fertilized egg does not immediately implant in the uterine wall after conception. Instead, the embryo remains in a state of suspended development for an extended period. This adaptation allows the female to rebuild her energy reserves, which become depleted during the prior 6 months of pup dependency.

Ecology

Sea otters are a keystone species whose role as predators play an important part of maintaining the health and diversity of marine ecosystems, particularly kelp forests and eelgrass beds. Sea otters in California are known to consume more than 70 species of invertebrates, including sea urchins, abalone, clams, crabs, mussels, and sea stars. However, each individual sea otter usually specializes in just a few specific prey types. They need to consume about 25-30% of their body weight each day to meet their high energetic demands, which has a cascading effect by preventing many marine herbivores from overgrazing kelp forests or eelgrass beds, which support biodiversity and sequester carbon. The only known predators of sea otters in California are humans. Though they are frequently bitten by sharks, they are rarely, if ever, consumed.

Cultural and Historical Context

Before European contact, sea otters were an integral part of the coastal ecosystem from California to Alaska. Archaeological evidence suggests that indigenous peoples have been coexisting with sea otters for at least 10,000 years. The arrival of European and American fur traders in the 18th and 19th centuries had a devastating impact on sea otter populations. The high demand for sea otter pelts on the international market drove California’s otter population from between 15,000 and 20,000 in the 18th century – to the brink of extinction by the early 1900s.

Date modified: January 2025

This animal can be found at the Aquarium of the Pacific

Primary ThreatsPrimary Threats Conditions

Threats and Conservation Status

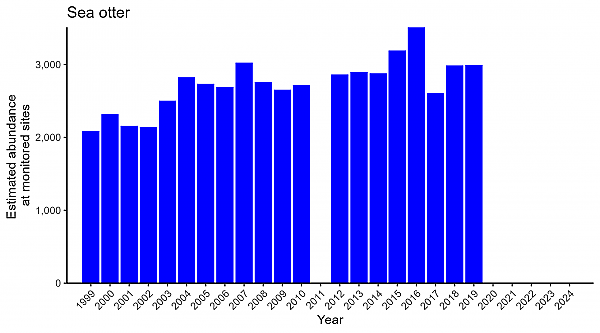

In 1938 the last few remaining southern sea otters numbered only 38 individuals near Big Sur in California. The Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 and being listed as Federally Threatened in 1977 has subsequently made any killing, hunting, or harassing of these otters illegal, but they still face significant ecological threats and their recovery from near extinction is at best partial. The population data for southern sea otters represent a statewide number based on annual aerial surveys and shore-based censuses. Because these otter counts represent the entire population, we show both the total population size without regard to region since 1999.

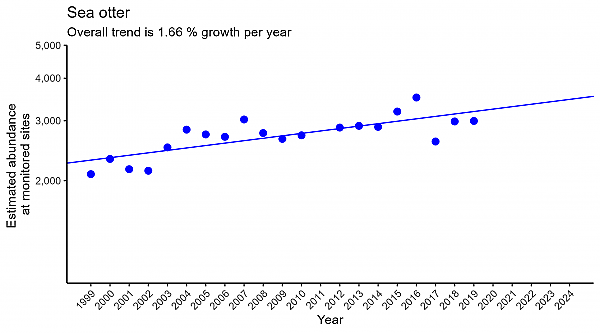

After an initial extended period of recovery, the population of southern sea otters is now slowly increasing at an annual rate of 1.6%. It has not been able to climb significantly above 3000, and otters remain absent from the majority of their historical habitat in California. There is growing interest in actively moving sea otters into Northern California and Oregon. Active intervention may be needed because otters have not been able to extend their geographic range naturally for about 20 years, likely due to high shark bite mortality at the range peripheries. In addition, much of their favored kelp habitat has been lost, and that hinders their ability to expand their range to its historical extent.

The possibility of seeing otters once again throughout all of California has inspired a vision of statewide recovery. Because otters help maintain kelp ecosystems by holding urchins in check, any statewide recovery of otters that can be achieved may facilitate statewide recovery of kelp ecosystems. However, there is historical evidence that in the past otters have had a negative impact on crab fisheries and if there is to be statewide recovery of otters, potential conflict with fisheries will need to be considered. Despite localized recovery of sea otters in central California, there remain numerous threats such as pollution in the form of oil spills, domoic acid poisoning, runoff from terrestrial lands, as well as direct human harassment, infectious diseases, climate change, and changes in prey availability.

Population Plots

Data Source: The data were collected in collaboration by the U.S Geological Survey, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the Monterey Bay Aquarium. It is publicly available data that captures the distribution of Southern Sea Otters along the mainland coast and on the San Nicolas Island for the last 40 years. This census entails both aerial counts and ground-based counts closer to the shore. Details of survey methods, as well as data and metadata from this survey and surveys from previous years, are available in https://pubs.usgs.gov/ds/1118/ds1118.pdf.